Delivering new product lines quickly with low capital investment

June 2021

By Simon Copley – Mechanical Engineer at 42 Technology

For many manufacturers, the manufacturing equipment used to produce their products represents significant investment, which is typically amortised over a long period. Yet consumer demand evolves over time, and this puts pressure on the manufacturer to respond with new products.

Unlocking the hidden potential of your manufacturing assets

Responding to the need to launch something new and different in the market might involve a long development process. Not to mention a significant investment in production assets. At the same time, the equipment used for the previous product might become underutilised or entirely redundant.

This creates a conundrum:

"How to find a way to manufacture new products without incurring large expense in acquiring new production assets?"

An ideal solution is to be able to make the new products using existing production equipment. Not only can this lessen the financial and technical risks in bringing a new product to market, but it can also reduce the development time. It will also shorten the lead time of a new product launch. And if it’s not guaranteed that the new product will be a success, then this would be a cheap route to test it against the market with minimal investment risk.

The holy grail is to be able to use the capabilities of the existing production assets to drive the innovation of the new products. This is a big reversal on the standard approach to launching new products. Namely, to first fix the design of the product and then source or design the production method. Installing new assets - with associated capital investment and delays - to meet the new product’s requirements.

This approach is not without its challenges

Letting the capabilities of the asset (such as a piece of production machinery) determine the nature of the new product presents two significant issues:

- Production assets are often highly specialised and tuned to their current application. And so their capability to create a wider variety of products often appears very limited. As such there’s the belief, often not always justified, that existing assets cannot be used to make much other than the current product.

- New product requests come from product managers who are market-focused rather than production-capability focused. And the attributes of the new products might not overlap with the capability of the existing assets.

The initial situation, with no easy solution in sight!

The initial situation, with no easy solution in sight!

These two challenges relate to the capabilities of existing assets and the manufacturing requirements of new products, respectively, with no obvious solution in sight.

In this situation, a powerful approach to bridge the requirements-to-capability mismatch is to apply the deceptively simple principles of asset driven innovation.

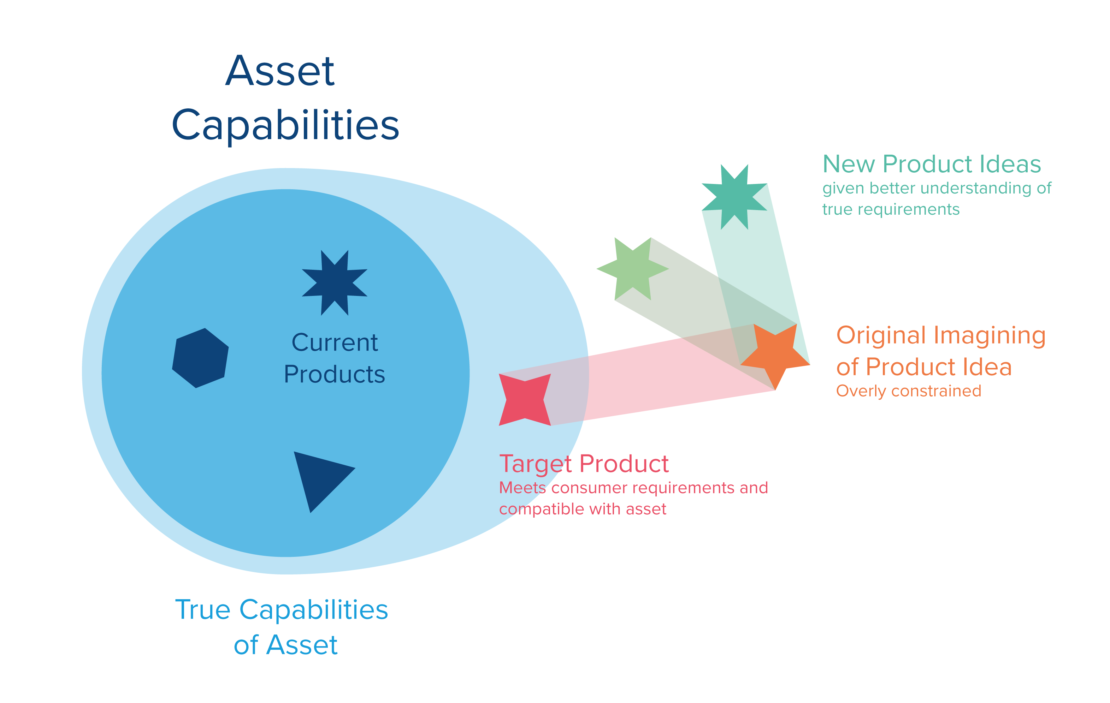

Asset driven innovation is based on widening the definition of what the new product is required to be. And in parallel with widening the understanding of what the assets are capable of, until there is common ground between them.

The idea behind asset driven innovation: expanding both sides until they meet in the middle.

The idea behind asset driven innovation: expanding both sides until they meet in the middle.

42 Technology has successfully used the methods described in this article for our clients, predominantly within the food and drink industry. But in general, the approach is applicable across many industries.

Exploring the possibilities of new products

Given that the end goal of the process is to match new product requirements to manufacturing capabilities, it’s important to understand your exact requirements for new products. The main aim of this step is to systematically identify how to widen the requirements side of the top-level challenge.

A list of product requirements may appear to be set in stone, but it’s important to determine what level of flexibility is permitted in each requirement. Challenging the list of product requirements is important, because they typically originate out of one of the two following scenarios:

- Consumer insight work or in-depth market research has identified specific market opportunities. And one or more detailed requirement specifications have been written in response.

- A relatively undeveloped list of requirements has been drawn up, based not on market research but on beliefs and aspirations within the organisation.

Key steps

The key steps to take in either of these scenarios are first to explore how well such new products have been defined, capturing information and opinion from relevant (and typically internal) stakeholders. Several useful approaches to explore this are outlined in this article.

The next step is to abstract the requirements as far as possible into “solution-neutral” product requirements, rather than focusing on any specific product implementation. An extreme example would be to compare the requirements for a snack forming production & bagging system:

"Every snack coming out the forming machine must have similar mass"

and

"The filled bags of snacks must have a similar mass"

The first requirement is overly constraining, because making a perfect snack forming machine might be far more complex than weighing a portion of snacks at the bagging stage. The second, solution-neutral requirement doesn’t rule out this easier option.

Compiling a list of true product requirements allows the team to understand what the broad “targets” are for the new products, and subsequent asset driven innovation work can aim towards these “targets”.

This stage does not directly result in new product concepts that are guaranteed to work with the asset in question. Instead, it provides a series of criteria that can be used by the team to recognise any useful and desirable new products at a later step in the process.

How to explore the capabilities of the current assets

It’s important to identify a suitable asset to focus on. Good candidates include those that are currently underutilised, such as:

- Mothballed production equipment.

These are probably designed for a product that has since been discontinued, or equipment designed for pilot lines that are now redundant.

- Assets in use but with spare production capability.

For example, the maximum throughput of the line might be higher were it not for constraints imposed by a specific piece of equipment. Or perhaps capacity exceeds end-customer demand. It may be possible to use one asset for multiple products, either by alternating batches or producing product variants side-by-side on a single line.

It may appear obvious what the asset in question does. However, it’s frustratingly easy to neglect secondary functions that occur ‘under the hood’ or unrecognised latent capabilities that aren't being exploited.

Deconstructing the process

The end-to-end process should therefore be deconstructed to explore what the equipment achieves at each step of its operation. For example, a machine used to form a food product might carry out a variety of actions almost simultaneously:

- Dosing uncooked ingredients into position

- Compressing food into a specific shape

- Heating the food to a controlled temperature

- Regulating humidity

Each of these functions is important and should be explored individually rather than considering the equipment function as a whole. The aim here is to explore what capabilities the asset has apart from those used for making the current product.

For example, you may want to think: what could be possible without any changes except for adjusting operating parameters like temperature?

Consider which minor/major modifications could widen capabilities further:

- Can we reconfigure anything to enable processing of other materials/ingredients?

- How could each processing step be reordered for different results?

These abilities should be collected into an asset capability ‘toolkit’ and shared with the whole team. Where any equipment modifications are needed to unlock new or unused capabilities, the relative investment needed to achieve each should be estimated.

It’s useful to discuss these ideas with a range of people at this stage. Involving machine operators, the equipment manufacturer, and other relevant employees will widen the conversation. But watch out that the scope of work is not narrowed by members of the team bringing pre-conceived views and perceived limitations about what is possible.

Both ends meet in the middle

The final step is to bring both halves together and generate a range of concepts that align the outputs of both sides of the challenge: both manufacturing capability and the attributes of the aspirational new products.

Piecing together concepts works well using a group approach. Start with a cross-disciplinary team with a broad understanding of both product design and manufacturing. This would ensure that ‘far-out’ ideas are not missed.

Members of the group will normally fall into one of two camps: marketing experts and manufacturing experts. It’s valuable to include somebody with exposure to both sides, who can straddle the two groups and spot the places where potential overlap might occur. In addition, they might even add value by acting as an “interpreter” between both groups.

Keeping an open mind in the early stages is also key. We’ve had our most successful innovation workshops when we take a ‘no idea left behind’ approach. The aim here is to think up product variants inspired by the low-cost degrees of freedom identified in the manufacturing capability exploration. And also check that these are acceptable in the context of the output from the product exploration.

Some grey areas will probably lead the team to iterate back to the product requirements and asset modifications, and explore some areas in greater detail to target. This would be a plausible manufacturing configuration for the asset, producing a product with genuine market appeal.

What next?

A great result at this stage will be to have identified a large number of concepts with a ‘reason to believe’ behind each. But developing all to a reasonable level of detail can take a long time.

Instead, a useful triage step is to assess each early-stage concept against a set of pre-determined evaluation criteria that represent the attributes of a successful product. Not only will this rule out some concepts, it will also focus the team on the specific attributes or weaknesses of the remaining concepts. Then identify where it would be best to target the effort.

The best development route will likely be to focus effort on the strongest concept for reworking the asset. Give emphasis to uncovering any ‘showstoppers’ as early as possible, minimising wasted effort. It may be appropriate to pursue development of several concepts in parallel. Especially if one is a high risk-high reward and the other is a more incremental low risk, low reward alternative.

Ultimately, the aim of asset driven innovation is to launch a new product without requiring a long lead time or substantial investment. The key to success is to take the structured and open-minded approach and probe the challenge in an intelligent way.

Image source: Andrew Neel on Unsplash

If you would like to find out more please contact Simon:

answers@42T.com | +44 (0)1480 302700 | LinkedIn Simon Copley

Simon is a highly practical mechanical engineer with a multidisciplinary technical background. Simon has used his skills in projects as varied as designing assembly jigs to reduce the manufacturing cost of an industrial communications device, developing tests to assess the durability of a surgical device, and evaluating the strength of IP held by a large manufacturer of consumer products.

Share this article:

Related Articles

Manufacturing & Automation, Industrial

How to bring sensing in manufacturing out of the lab and onto the line

Manufacturing & Automation

Digitalisation in manufacturing - building on the foundations of good data

Manufacturing & Automation

Food & beverage industry - trends to be aware of in 2024

What will you ask us today?

We believe in asking the right questions to drive innovation; when we know the right questions, we generate the ideas to answer them.