Digitalising the crown jewels

April 2021

Digitalisation promises flawless clarity; perfect decisions based on crystal-clear information, at the right time and in the right place. But this perfect information must be cut from raw data, and of all the data that’s available, how do you know which streams will be the most valuable? As with any expedition, a strategic exploration process is more likely to unearth new and bigger gems.

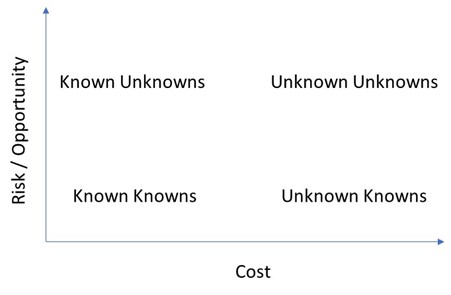

Donald Rumsfeld’s categorisation of our states of knowledge may be a bit hackneyed these days, but in any prospecting field it still holds relevance. Digitalisation is still very much such a field, filled with promise as well as uncertainty. Currently used data streams have likely evolved to be “good enough” as sources of information on which to run operations.

However, there is no guarantee that these information “nuggets” are optimum, and that even better information diamonds don’t lie in hitherto unexplored data seams. Information diamonds that could entirely re-focus operations and customer engagement and ultimately make the bottom-line sparkle. Delivering on the promise of digitalisation therefore requires the strategic exploration of these newly feasible data streams to increase the probability of finding the diamonds. Rumsfeld’s categories form a useful starting point in the exploration map:

Known Knowns

The logical place to start is with the Known Knowns. This is digitalising the data streams that are already being collected and used to make decisions. It’s the low cost, low risk entry point. Even this first step requires some prioritisation and those data streams that have the most value or are most subject to costly errors, perhaps from manual input, should be top of the list. Often the approach taken here is to just use data feeds available out of the box. While this may be valid for some cases, seemingly suitable substitutions may not always be directly analogous. Measuring how hard the pickaxe is swung is not the same as tonnage produced. Even in digitalising proven, manual processes there may be scope for optimisation. Higher frequency and greater accuracy can often be obtained for free.

Known Unknowns and Unknown Unknowns

Next, efficiencies can often be realised by mining both the Known Unknowns and Unknown Unknowns simultaneously. The former by tackling in priority order, the wish-list that’s been languishing in the drawer. And the latter by a try-it-and-see approach. In both categories the gems are often deeply buried and require some extra-effort unearthing. After all, these are the data sources for which there isn’t an easy off the shelf solution to detect them.

Exploring these Unknowns effectively usually requires two parallel techniques – scale and resolution. Low-cost development kits (“dev-kits”) and modular computing and sensor systems are now available that can greatly aid measuring challenging but valuable properties. Using dev-kits to test at scale can rapidly help define the system that works for that specific application without having to do bespoke design and prototyping. Coming from the other side, generating over-high resolution data helps home in on the exact technical specification required. Here trials should be conducted by implementing over-spec’d data acquisition systems to understand what specific data is useful.

For example, in a video analytics system it would be best to start with a high-end camera, analyse the data and determine what camera is actually needed. It’s worth noting that neither dev-kits nor over-spec’d, costly hardware is likely to be suitable for in-service industrial use. And that bespoke systems needs to be part of the plan in most cases.

Exploring the Known Unknowns in this way often throws up Unknown Unknowns. The data sources that weren’t even suspected of providing value, but actually turn out to augment and enlarge the information from other data sources. It’s well worth allowing creative freedom to explore these seams that only become accessible with the new technology as this is where the biggest gems are often found.

Unknown Knowns

The final category, the Unknown Knowns, is often neglected as it is the hardest to define. This is all tribal knowledge implicit in the business. The diamonds buried in all the data spoil. However, sifting through this often reveals valuable sources of data and information that has real business and customer value. Technical soul-searching is often required here:

What data is actually providing the value?

This links to the Known Knowns, but tends to delve a little deeper:

What data is really creating value?

What would happen if we had it at a lower or higher resolution?

What’s the optimum point in the value equation?

Questions like these may seem straightforward but often have non-trivial answers. The answers clearly link directly to the technology that gathers the data. Defining the optimum information point can have quite profound implications on system design and cost. Often the best way to explore these rich but vast seams, in our experience, is to get real feedback from the field through testing feasible options.

Where we are all familiar with the concept of minimum viable product, the use of the “maximum feasible prototype” comes in to play here. This is a “looks like” prototype that is not in any way production intent and purposefully contains superfluous functionality. It’s just not yet known which will turn out to be the sharp pickaxes. The use of virtual reality and other rapid iteration tools can also play their parts here. “Prototypes”, whether real or virtual, should be designed to enable testing of different functional attributes in real use cases. To get insight and feedback as to what “works”. To uncover the Unknown Knowns. An agile approach and clever design to minimise re-design between iterative test cycles and production help with efficient exploration here.

Clearly there is no hard distinction between each category of Known and Unknown, or set methodology for how they are each best explored. However, a strategic approach and suitable application of technology will maximise the probability of finding the crown jewels and making your business sparkle.

Down-selecting to the perfect mining tools

In creating the globally digitally connected product for an industrial client it was known that remote asset location and status updates derived real value both for them and their customers, enabling servitisation to their global customer base. What was unknown was which form of radio communication their customers would be most comfortable employing (e.g. short range to a phone or long range to a cell tower). And which ones would work in the various environments their products are used. Interaction with other technical requirements such as battery longevity were also uncertain.

Simulation and local proof-of-principle tests suggested a list of candidate radios, but only real-world verification could determine in-field performance. Initial alpha-prototypes were designed and manufactured, at considerable expense, incorporating all candidate radios (and associated antennas etc), and the ability to remotely turn these on or off. Testing of signal strength, connection reliability, data granularity and frequency and power draw over the range of customer and client site use cases using different radio combinations indicated the optimum set to be included in the production design. Had it not been for this up-front investment, it is highly likely that a sub-optimum technology set would have been specified. This would have reduced the product value or necessitated further R&D investment. In either case reducing the ROI.

We have seen similar technology choice dilemmas across a range of industries, each where the final specification can really only be addressed by field testing the options. What seems a simple selection question is rarely straightforward to answer.

If you would like to find out more please email us: answers@42T.com

Share this article:

Related Articles

Connectedness, Industrial

How embedded edge devices can unlock machine learning for industry

Connectedness, Sustainability

Green claims - how recent EU regulations can help futureproof products and improve profitability

Connectedness

Unleashing the benefits of energy harvesting from electrical supplies

What will you ask us today?

We believe in asking the right questions to drive innovation; when we know the right questions, we generate the ideas to answer them.